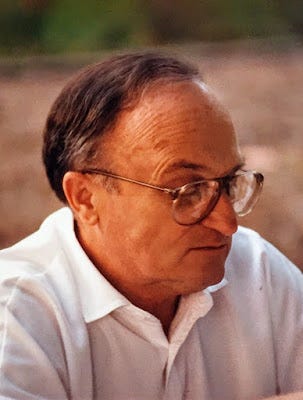

This essay is from May of 2020 and was written upon the death of my grandfather. I share it on this Father’s Day, slightly modified, for a new audience.

When I was 11-years-old, I went to Atlanta with my grandfather for college basketball’s Final Four. As we walked into the hotel restaurant for breakfast one morning, I saw Tom Izzo, the head coach at Michigan State. By then, Izzo had won a national championship and had been named National Coach of the Year three times. He was so successful in the NCAA Tournament, people called him “Mr. March.” He was later inducted into college basketball’s Hall of Fame. When I saw him, my 11-year-old eyes got really big.

The strange thing was that, when Izzo saw us, his eyes got really big. He came over to my grandpa: “Dom Rosselli?” They went back and forth a bit and, eventually, Grandpa introduced me. I don’t remember much of what Izzo said, but I do remember he finished with something like: “You know... Your grandpa… He’s the real deal.”

I guess I did know, taken aback as I was. In his time, Dom Rosselli was a college basketball coach himself. He was a legend actually. In fact, the day we met Izzo, Grandpa had won 357 more games than him.

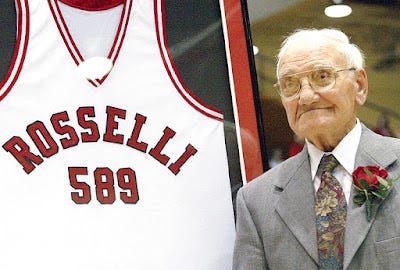

Dom Rosselli coached for 38 seasons at Youngstown State University. He was one of the winningest coaches in the history of the game. Throughout the 1950s and 60s, several organizations named him “Coach of the Year,” including his 1958 “Italian Coach of the Year” award (which has always made me smile).

Not long after his retirement, Youngstown State painted “Rosselli Court” on the floor of their arena and, several years later, they erected a statue of him outside its door. When he died, it was on ESPN. Flags in the city of Youngstown were flown at half mast. Dom Rosselli was very much the real deal.

Growing up, both of my grandparents lived relatively close. After the Final Four, we visited with my other grandparents to talk about the trip. My Grandpa Johnny didn’t move in the same circles as Dom Rosselli. While Dom was becoming a legend for the city of Youngstown, John Slovasky was making it smoke. For 35 years he worked in one of its famous steel mills. As a kid, I was just told that Johnny had “worked at the mill,” and so I pictured him as a man of the blast furnace and of molten iron — a hardened laborer. It turns out he did bookkeeping in the office. And when the Youngstown steel industry was decimated in the late 1970s, Johnny was one of the 40,000 or so who lost their jobs. For years afterward, he wallpapered homes to make a living.

I knew my Grandpa Johnny when he was an older man and, as I knew him, there wasn’t much to him. He was a quiet man, a calm man. He was a Buick man. He liked to talk about routes and avenues, about “the construction over on Tibbetts Wick.” He could always remember a good restaurant about halfway to someplace, but he could never remember its name. He hated the New York Yankees. He had one of those senses of humor where you really wanted to be sure your girlfriend liked you before you let her meet him. He liked John Wayne. He fixed things with duct tape. When he died, it was not on ESPN.

A few years before his death, Youngstown State made bobblehead dolls of Dom Rosselli. You can still occasionally spot them among the decor at various Youngstown restaurants. When I opened the box, I noticed that Grandpa had autographed the back: “Coach Dom Rosselli.” I’d never seen him autograph anything and I was struck by it. Of course, Grandpa was a sportsman. His living room had more cups and plaques than my small college’s trophy room. And yet, after all the hours I’d spent there, I’d never heard him tell even a single story about those trophies. Every story I’d ever heard about those days I’d heard from someone else — former players who knew my dad, newspaper columns, Grandma. That’s why, when I met Tom Izzo, I couldn’t really attend to the fact that my own grandfather had outdone him by several hundred wins. In my mind, that’s just not who the man was. He wasn’t “Coach Dom Rosselli.” He was just my grandfather.

John Slovasky never autographed anything. He didn't even sign his checks correctly. As a matter of fact, his name was not Slovasky at all. In the 50s, just after getting married, he decided that his family name (Slovkasky) was a bit of a mouthful, so he just started going by Slovasky. But instead of legally changing his name, he just shrugged and began writing it differently. Eventually, his entire identity was fudged over and he just became John Slovasky.

There is something very Johnny about that, about that shrug of indifference. When he was in the Azores during the war, he needed to swim to retrieve some nurses into a lifeboat. But he didn’t know how to swim. “I was told to do it,” he shrugged. As I knew him, Johnny was sheer straightforwardness. His life took place right in front of him. Things didn’t need to be overthought.

When you reflect on your father or your grandfather, there’s a temptation to talk about the ways they embodied some sort of bygone strength. Oddly enough, my grandfathers taught me far more about weakness and about losing than they did about strength. Dom had not a word to say to me about his 589 victories. To me, when he talked about basketball, he talked about losing at it. There were a few seasons when Grandpa could have won a national championship. Across a couple different divisions, he coached in 13 postseasons. The year Youngstown was the tournament’s overall #2 seed, they were upset in what we now call the “Elite Eight.” There were seven times he coached in what is now the “Sweet Sixteen.” But a national championship never came. I once asked him: “Grandpa, how many games did you win in your career?” “I lost several hundred.”

When he was drafted, Johnny told the sergeant at the draft board that he had no interest in combat. A year earlier, he had to read to his mother, who didn’t know English, a letter from the Army announcing his brother’s death. He had no reverence for war or the grittiness that’s supposed to go with it. War was not a moment of strength, but of fear and trembling. War killed his brother and broke his mother. He never told stories about the war unless they were forced out of him.

One of the unspoken lessons of my grandfathers, as I gather it, is that strength is far less important than we often think — that the real contours of who we are are formed, not in our strength, but in our failure and our fear. Dom Rosselli was one of the best coaches in the history of college basketball. “They wanted to fire me,” he joked in an interview, thinking of a bad stretch. He just laughed: “I could find another job... maybe make more money. They’d probably be doing me a favor.”

Today, we live in a meritocracy — a society that insists we must hustle to do singular and exceptional things. I often find myself desperate for everything I do to be taken seriously. Johnny didn’t want to be taken seriously. He wanted to be at home near his wife. He wanted to read the newspaper. He wanted Derek Jeter to strike out. One of our central dogmas is that we have to be strong and independent. Johnny’s later life, on the contrary, was one of physical weakness and radical dependence upon his wife. His world was one where even just sitting and standing were extraordinarily difficult. The insistence that we “not mention those kinds of things” is precisely the lie of the meritocracy — the false dogma that the only beautiful part of life is the part that’s lived in strength. On the contrary, Johnny’s weakness was precisely the space in which it became abundantly clear how much he was loved. In the last months of his life, as my Bubba would help him get situated around the house, she’d sometimes stop for a hug. “Why do you want to hug me?” he’d ask. Screaming, because he could hardly hear: “because I love you!”

Grandfathers are supposed to be known for their stories. But neither of my grandfathers were the sit-you-down-and-teach-you-a-lesson type. They passed their wisdom on in the ordinary doing of their lives. The things I remember about them are ordinary to the point of insignificance. I remember the way Johnny picked chocolates off a tray with his fork. I remember the yellow and blue on Dom’s Cub Cadet lawnmower. There were no real lessons here. There was only abiding presence. It was on you to notice it.

As I look back, it seems like my grandfathers taught me the odd lesson nobody ever wants to tell a story about. They taught me that the far more significant moments in life are the moments when you lose, when you never win a championship, when you get laid off, when you’re not the real deal. They taught me that, compared to the family itself, a family name is interchangeable, that it deserves nothing more than a shrug, even if it’s memorialized on an arena floor. They taught me that you come into contact with what’s really important when you’ve been humbled, or when your body is broken, or when you’re afraid, and not when you’ve won by 20. Life is very rarely about the impressive stuff ― about blast furnaces or 589 wins. It’s far more often about humility and weakness and presence.

Neither of my grandfathers were the sit-you-down-and-teach-you-a-lesson type. The lesson was in the ordinary doing of their lives. It was in the sitting and in the standing. It was in a good restaurant about halfway to someplace. In 589 wins. 388 losses. Zero national championships. It was in humility. Weakness. Presence. And it was on you to notice it.